Dunstable Priory in 1283 :

The oldest recorded mechanical clock

By Omer Roucoux

Previously published

in the Newsletter of the Dunstable and District Local History

no18. p.114 – 115 (September 2002)

In the year 1283 the chronicler of the Annals of Dunstable Priory (1) reports :

Eodem anno fecimus horologium quod est supra pulpitum collocatum.

This can be translated : In the same year we made the ”horologium” which is placed above the ”pulpitum”. Two words have not been translated as they need some interpretation.

The Annals report only important domestic affairs and external historical events and are not concerned with minor matters. The making of a ”horologium” was therefore an event of unusual importance and should not be confused with the acquisition of an ordinary water clock or Clepsydra, which was then the common time keeping instrument.

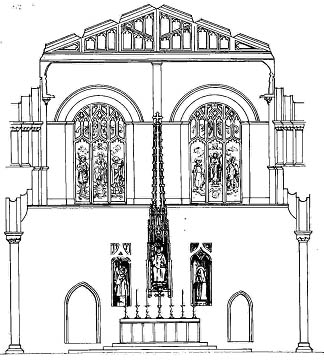

In St Albans Cathedral the ”pulpitum” is a big wall from floor to ceiling, completely decorated with statues and backed by the organ. Another one separates the choir from the shrines of St Alban and the Lady‘s chapel. So the horologium placed above the pulpitum was most likely a mechanical clock; it would have been a very awkward place for a waterclock. But was it the first mechanical clock at all?

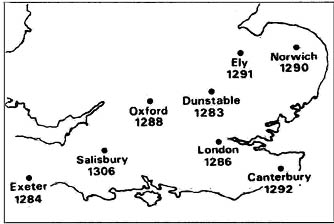

It is certain that it is the oldest mentioned in the documents and it is possible that we have lost the reference to older clocks of the same type. The earliest documents from this period use the same name 'horologium‘ or ‘novum horologium‘ for a mechanical clock : Exeter in 1284 and St Paul‘s Cathedral, London in 1286 are the first two following Dunstable. With the others installed before 1300 at Oxford, Norwich, Ely and Canterbury they were not too far removed from Dunstable, in time and distance, so that ”the probability nearly becomes certainty, that, at the beginning of the dark era 1276-1310, in one of the places of Southern England the principle of the mechanical clock came to light. Only we do not know yet precisely, when and where, because we do not have anything similar to the Dunstable Annals, fortunately preserved.” [2, p.195]

Who built this clock ? In the Middle Ages monasteries were the centres of knowledge and all the skills were traditionally cultivated. But the Augustinians were Regular Cannons, that is priests living in a community. Their life was dedicated to pastoral care. There must have been a number of lay people dedicated to material work, such has building and maintenance, cooking and looking after the hosts and the sick. Some of them were smiths and could have developed the refined skills to build a new mechanical time keeping device. (4)

If this is so the Annals could proudly proclaim : ”We build a Horologium, a Mechanical Clock”

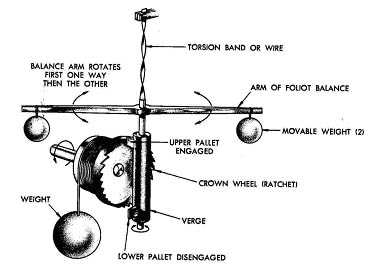

What the clock was like is a difficult question to answer. The first mechanical clocks were certainly weight driven, they did not have a clock face and their purpose was only to strike a bell at regular times. This was actually the main purpose of a new kind of clock, to call the canons to their prayer duties, day and night without one of them having to stay awake. Actually some water clocks were already provided with a striking bell. The name ‘clock‘ meaning nothing else as the word comes from the French‘cloche‘ which means ‘bell‘. To slow down the falling of the weight there was an escapement probably of the ‘foliot‘ type as this is the oldest type recorded. This consisted of a vertical axis (the verge) fitted with two pallets. When rotating back and forth, the pallets released the ”crown wheel” (rachet) tooth by tooth. The crown wheel with its triangular teeth was driven by a weight, and probably connected to the clock hand by gears of some sort. At the top of the bar there was some kind of mass slowing down the foliot by its own inertia. Since this mass had a period very difficult to control, the accuracy must have been very low and an error of up to one hour a day could be expected.(5)

A manuscript of 1271 contains the following [6] ”Nor is it possible for any clock to follow the judgement of Astronomy with complete accuracy. Yet clockmakers are trying to make a wheel which will make one complete revolution for every one of the equinoctial circle (a day), but they cannot perfect their work.... The method of making such a clock would be this, that a man make a disk of uniform weight in every part so far as could possibly be done. Then a lead weight should be hung from the axis of that wheel, so that it would complete one revolution from sunrise to sunset...” No trace of an escapement in this description but how else could it be slowed down? It is only with the discovery of the regular motion of the pendulum, in the middle of the 17th century, that the ticking of the escapement started to give a correct time reading.The next improvements were the introduction of a spring as he driving force (Germany, about 1500), the discovery of the regular oscillation of the pendulum applied to clocks around 1650, and the invention of the ‘anchor' escapement, about 1670, The rest of the story is that of refinements of the basic principles and miniaturisation making watches possible.

Footnotes:

[1] Annales Prioratus de Dunstaplia : The Annals are the chronicles of the Augustinian Priory of Dunstable. They begin with the death of Christ and the author uses various sources, but from 1210 they are written by the 4 th prior, Richard de Morins, until some years before his death in 1242. Before 1202, when Richard was elected prior, there is nothing related to Dunstable, only a few lines, each year, reporting the main events of British and Church history. Later on they are most interesting when they report the Priory business and the events and problems of the town.

[2] This paragraph is based on ideas expressed by C. F. C. Beeson : English Church Clocks 1280-1850 p.13-15 and the long comment on this article by Hans Von Bertele : The Earliest Turret Clock ? in Antiquarian Horology, Vol 10, 2, Spring 1977, p.189 - 196.

[3] About the ‘Stone screen‘ behind the present altar in Priory Church see the description of its discovery by Worthington G.Smith in Proceedings of the society of Antiquaries, April 7, 1910 p. 153-157 with drawings of the inside and the outside of it.

[4] David KNOWLES : Religious Orders in England, Vol.1, ........

[5] From Clocks and Watches, prepared by the Science Service, Nelson Doubleday Inc. 1965, p.18.