Orange Rolling

On Dunstable Downs

By Rita Swift

Orange Rolling, which used to take place at Pascombe Pit on Dunstable Downs every Good Friday, seems to be a custom unique to Dunstable.

In the north-east of England there are events called Pace-egging or Pace-egg rolling, pace being a dialect form of the word Pasque, meaning Easter. Could Pascombe really be Pasque Combe?

Other districts chose to roll eggs down grassy slopes, eggs being a symbol of the stone rolled away from the tomb where Jesus was laid.

Could it be that Pascombe Pit is so vast, eggs would not be seen easily and become lost in the undergrowth? However the origin remains a mystery.

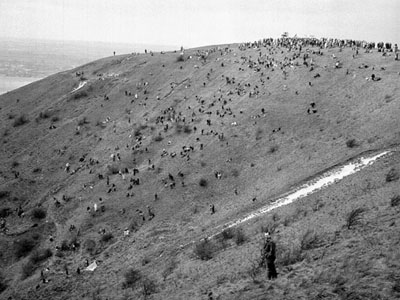

The Mayor of Dunstable throws (rather than rolls) the oranges at Pascombe Pit in 1953

The Dunstable Excelsior Band, Borough Prize Band, the Salvation Army Band, a Punch and Judy Show and various stalls provided regular entertainment. The vendors' cries of “Three a penny! All lovely and luscious like wine!” could be heard loud and clear, although wine was not the word which first came to mind if one was hit by a rotten, juicy missile!

In 1899 Lady Teasers were on sale together with the oranges. These appear to be a rubber item filled with water, an early form of water pistol. The vendors considered Good Friday the best day of the year, as customers were willing to buy fruit no matter what the size or condition.

Youngsters made up the majority of the crowd, from the town and surrounding villages. They did not care about being hit or bruised or tumbling down as long as they returned home with their juicy prizes.

But also among the orange hunters were always several “old hands,” whose object was to turn their fruity shower into hard cash as soon as possible. Various methods were adopted to make themselves conspicuous targets for those rolling the oranges, including turning their coals inside out, wearing enormously tall and antiquated top hats, jumping up and down, waving their arms and shouting and so-on.

A continuous volley of oranges aimed in their direction was deftly bagged, handed to a younger assistant, and hawked around the neighbourhood the following week. Many eager youngsters quickly learned to position themselves behind these “old stagers” and reaped a greater part of the harvest aimed at them. Towards the end of the afternoon a few catchers bore the oranges back to the top of the Pit in their jackets and turned a profit by underselling the bona-fide vendors.

But everyone took it all in good part and unselfishness was characteristic at this event. One example was an occasion when a tiny girl, too young really to safely take part, was struck by an orange with such force that she was kn ocked over and the orange rolled away. A young boy, not much older himself, raced to retrieve it and returned it to the little mite. A newspaper reporter watching the young hero was pleased to note that by the end of the afternoon all his pockets were crammed to bursting. A just reward.

Occasionally some toff, with a conspicuously glossy “tile” (top hat), would venture among the throng of merry-makers and within a couple of minutes some well-aimed rotten oranges would have marred its glory forever. Caps or a hard- felt bowler were the regulation headgear for males, as this was the one afternoon when anything within the law was allowed. No self-respecting “bobby” would ever dream of interfering should anyone complain of being hit, or they would have had the crowd to deal with. Good manners prevailed and ladies' hats were not targeted.

At the foot of the Downs there were various stalls, swing-boats and coconut-shies and a muscular woman laboriously grinding out, on a powerful organ, the comforting assurance that “Everybody loved by someone!” A regular visitor to this event was a blind pedlar who could be seen making his way with marvelously unerring footsteps perilously near the edge of the Pit.

In 1900 the wind was so fierce the vendors had to pitch their stalls lower down in a more sheltered place but that detracted from the fun. The Dunstable Gazette reported:

“A few courageous young people endeavoured to climb the Downs . Many of them belonged to the fair sex, and, as the wearing of bloomers has by no means yet become general, the wind played havoc with their skirts, and the result may be much more decorously imagined than described. No staid and sober journalist such as the writer of this article would ever dream of looking in that direction while the wind played such mad pranks with these ladyes faire; nevertheless it may easily be imagined that a wonderfully pretty display of multi-coloured petticoats was seen, while here and there a gleam of white, while the fair ones were executing most marvellous evolutions in frantic - but generally futile — endeavours to retain a serene and stately comportment.

“One musician who was brave enough to go serenely on, unmindful of wind, hail, rain or snow, was the man who ground out a sorrowful dirge on a hand-organ, while his pony meantime worked the merry-go-round. That organ was a revelation! With a perversity and ardour that no flay of the elements could quench, it continued an endeavour to grind out two tunes at once. Despite the fact that several pipes refused to fulfill their mission, and that others were two, three, or four tones flat, the old organ gave forth a mixed up medley of ‘Skylark and ‘Dolly Gray' which was really astounding. Around the organ-grinder there was gathered a group of some two-score youths, who jeered him incessantly on the result of his hard work; at first I fled to pity anyone condemned to such soul-distracting labour, but as I noted the calm indifference with which he treated the storm, discord and scoffs of the crowd, I came away awed rather, by such Spartan heroism.”

By the beginning of the 20 th century behaviour had started to change and several young ladies were struck with oranges mischievously thrown with great force into the crowd at the top of the Pascombe Pit, and some coconuts were even thrown down the Pit. The small number of police, inspite of such a large gathering, was usually successful in preventing any serious outbreaks of rowdyism, Unfortunately there were a few instances, including a coconut-shy, which was pelted and the stand raided by some boys. The Dunstable Excelsior Band fell victim and their programme came to a premature conclusion,

1914 was a quieter Good Friday as the Conservators had passed a resolution prohibiting vehicles to be placed on the Downs including the roundabouts; swings, shooting galleries and other amusements, which were normally to be found near the Volunteer Inn. Ice cream, mineral water and orange stalls were well patronised.

In 1940 a large proportion of the children were evacuees whose Cockney voices joined in “Roll ‘em down” together with “Roll out the barrel” . The vendors' vans were piled high with cases of fruit and all day the youngsters scrambled, tumbled and piled up in heaps of struggling arms and legs to gain the golden prize.

1941 - WAR SUSPENDS GOOD FRIDAY CUSTOM

This was the headline that reported the end of Dunstable's Good Friday tradition. The number of oranges available to roll down was infinitesimal as they were now an almost unheard-of luxury. For the first time since the orange became a popular fruit in England , a link with the ancient custom was broken.

Although Dunstable Chamber of Trade resurrected the tradition later, it came to an eventual end in 1968 due to Health and Safety regulation and the local traders deciding not to support it any longer

A little bit more general information.

From Quentin Cooper & Paul Sullivan, Maypoles, Martyrs & Mayhem Bloomsbury (1994)

There was only one real sport on Easter Monday — egg-rolling. It was a national pastime in Scotland , where the day was known as Egg Monday. Christian rationalisation said that it represented the rolling away of the stone from the tomb where Jesus had been prematurely buried. The chief object of egg-rolling was to see whose egg could go furthest without disintegrating, though sometimes there were goals marked at the bottom of the hills. The eggs were usually hard-boiled; but often they were not — it is surprising how far an unboiled egg can roll before splattering into a rock.

The defeated eggs were eaten, and their shells crushed to prevent witches from joy-riding in them. Unless you go to work on an egg-shell, a witch can sail out to sea in the unlikely vessel and conjure up storms to drown sailors, who were so perturbed at the prospect that they would not utter the taboo word “egg” at sea. There is in old saying, “ Break an egg, save a sailor”. This all stems from the idea that any food you leave can be used to work malign magic against you (as can nail-clippings, hairs, bits of clothing, and other personal detritus).

Egg-rolling remains a nationwide Easter tradition. The most hard-boiled roll-players head for Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire today — where rolling was revived in 1958 — or Avenham Park at Preston in Lancashire, which each year attracts in the region of 40,000 people and almost as many eggs. Among the many brightly coloured eggs rolling down the valley slope are some which are noticeably more orange and spherical than the others. They in are, indeed, oranges — an innovation thrown in to moisten the palate when it comes to eating the shattered contestants; although no orange is allowed to win the egg-rolling. The game never seems to have been particularly competitive at any of its locations, just a gentle bit of fun.