Markets in Dunstable

By Omer Roucoux

That Dunstable is a market town is indicated by its name.

Lambourne in his book Dunstaplelogia, published in 1859, commented: “The word Dunstable simply means a market on a hill, which exactly correspond with its situation; and I venture to affirm, that any Anglo-Saxon scholar in any part of the world give you the same answer, even though he never saw or heard of the place before.”

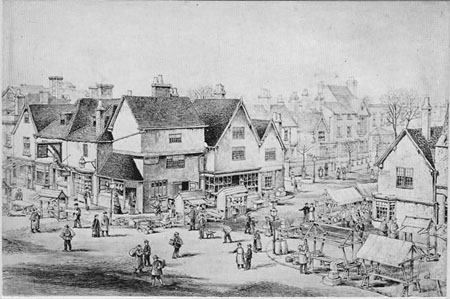

The drawing of the market in 1885 by Worthington G. Smith, ‘Sketch from my Work Room Window', is well known. This is only a section of it to show, in the middle background, the almshouses and, in the right foreground, the Nag's Head. We can also observe some of the six market stalls for the construction of which tenders were invited in April 1871.

The very beginnings.

Dunstable came to be where it is because it was a crossroads between two important Roman roads, the Wading Street , now High Street North and South, and the Icknield Way , now West Street and Church Street . The Romans had here a small station called Durocobrivis, where the travelling armies could stay overnight, find provisions and change horses.

When the Saxons replaced the Romans as the organising power in the country, the roads continued to be used but became very insecure and the villages withdrew away from them. Actually, the roads became the borders between villages. Further to the north of Stony Stratford, the Watling Street became, in A.D. 886, the official border between the Danelaw (territories controlled by the Vikings) and the Kingdom of the English Kings.

A crossroads was a natural place for country folk to meet for the exchange and sale of produce. There was no need for a settlement of any kind to be there first; think of the recent development and growth of ‘car boot sales', many of which started alongside a road where there was space to park cars for sellers and for visitors.

A similar phenomenon must have taken place not long after the year 1027. King Canute, the Dane, had completed his conquest of England and established over England the laws of the king of the previous century, Edgard the Peaceable. The land had settled down to a state of peace and prosperity. Goods could be exchanged, transported and sold across the country. Specialised and surplus produce could be transported and convenient places became markets. They were not located at the centre of villages as, for reasons of safety, these were purposefully situated away from the roads, but crossroads were ideal places for the purpose.

Houghton had been for many centuries Royal land and very likely there was a small market where local people exchanged their goods. The more important one, at the crossroads, had to be called something. It could have been ‘New Market', or ‘ Downs ' Market'. Why then Dunstaple?

Through the Middle Ages, in general, the village green, the market place, the crossroads had been marked by a cross or a pillar. This was sometimes a pillory, that is the stake where the criminals were publicly punished. Such a post was called a ‘staple', a word well understood by Saxons as well as later by the Normans .

In the oldest record (Beowulf, 950 AD) it means a post, a pillar of wood, stone or metal. The old form estaple has given the French étape, a halting place. Let us remember that a ‘trading post' is a market, and not a pillar, and a ‘staple diet' was originally the principal commodity of a food market.

In the 14th century staple was a legal term for a market, but the same meaning was in use a long time before. So we can understand people calling the new market place Dunstaple, ‘the market at the downs'. We must note that the spelling Dunstable was one of the many spelling varieties of the name. It was only used as official spelling of the town from around

1650.

The Middle Ages

In 1100 Henry I became king and while visiting his Royal lands he found problems of lawlessness around the old Roman crossroads. He decided to recognise this new Downs ' Market and, by the way, get some taxes out of it and encourage a settlement around it. Trouble at the crossroads was a threat to the peace of the highway but instead of solving the problem by force, as his father the Conqueror would have done, be founded a town.

It was a good place for other reasons. The king had a residence in nearby Houghton which was Royal land. The market would bring prosperity to the inhabitants and, at the same time, provisions would always be available for the court. It was easy access from the countryside all around, so cattle, meat, hides and other provisions could be brought without difficulty.

We do not know the date of this royal decision but we can say that by 1110 there was already in Dunstable a school important enough to have been given a teacher by St Albans . He was Geoffrey de Gorham and we know his story very well. He had been recruited in Normandy by St Albans school but he came too late to take his teaching post. While in Dunstable he organised a play ‘The Miracle of St. Catherine'. For the play he had borrowed precious ceremonial copes but these were destroyed in an accidental fire. To repair the damage done he entered the Benedictine order and in 1119, he became abbot of St Albans . We can assume that nine years is a minimum time between his entry in the religious order and his election as an abbot. That is how we can conclude that in 1110 Dunstable had already a well established population.

The foundation of the Priory is difficult to date, but the facts are quite clear and the story is told, in short, in a text ‘Tractatus de Dunstaple et de Hocton' dating from 1290: some 180 years after the events. ‘The lord king founded the burgh of Dunstaple and built a royal dwelling near that place. The burgesses were in all things as free as the other burgesses of the King's realm. The king held a market and fairs in the place. Afterwards he founded the church and by authority of pope Eugenius II! placed regular canons there. The said brothers he made lord of the whole burgh by charter and granted to them also many privileges.”

We know that the Augustine Regular Canons were already established in Dunstable in 1125, as Bernard, Prior of Dunstable, is listed with 14 other witnesses mentioned by name at an important chapter taking place at the Algate Priory.

The charter which is often given as the foundation document of the Priory was only given six or seven years later. The document bears no date but can be dated indirectly, by the names of the signatories, to 1131 - 32. Here follows the extract which mentions Dunstable market:

“You should know that I, Henry, King of the English, . . . have given to the Church of the Blessed Peter of Dunstable . . . and the Regular Canons there serving God. . . the whole Manor and Burgh of Dunstable with the land belonging to it, and its market, its schools and with all the liberties and free customs . . . But I retain in my lordship the houses and the garden where I lodge . . . . And I order that the men who shall come to the market of Dunstable have my firm peace in going and returning, and that any one disturbing them unjustly be fined £10. I also grant to the canons whatever they can reasonably acquire and that they and their men be free from the taxes and fines of... passage and stallage.”

The last few words mean that the canons were free from the general taxes imposed by the shire but could fix themselves and collect the taxes for passage — that is for the movement of goods and passengers on their roads — and for stallage — that is for erecting stalls and selling goods on a market.

Effectively the canons of Dunstable Priory kept control of the market with great care. It was an official duty but it was also to their advantage.

In 1221, market rules were drawn by the Prior in consultation with the burgesses of Dunstable. These are the earliest recorded rules in the country. They are written in medieval Latin and can be translated as follows:

Laws and Customs of the Town (Customale burgi).

1. Every burgess may rise on his property a windmill and horse mill, a dovecote, a bakehouse, a hand mill, a malt kiln and also a woodstack and dungheap unless the woodstack and the dungheap are a nuisance to the King's highway or to the Prior's market, in the opinion of the loyal men of the Town.

2. To those dwelling in the shops, it is not allow to brew in them for danger of fire; it is not allowed to them either to make pigsties outside their doors or to fix stakes in the ground without permission of the bailiff.

3. Butchers are not allowed to throw blood and filth of the animals which they kill in front of their houses or elsewhere in the street as a nuisance to the neighbours or the market.

4. The Townsmen or strangers who, on market day, set their stalls in the market must remove them at the end of the market (the same day).

5. The goods of any person killed or any person who runs away shall become the property of the Prior.

6. Traders of this and other towns must not buy foodstuff before the first hour (sunrise) nor go outside the town to meet sellers.

7. If a purchaser buys by the cartload anything that is usually sold by retail he shall not be allowed to diminish the number or sell it on the same day at a higher price.

8. Bread made for sale at a farthing (¼d) must not be refused to someone who offers a farthing and the same for ale when four gallons are worth a penny (d).

9. The regulations about ale (price and quality) are not enforced where a sign is not exposed outside.

10. When a widow gives up her “free bench” (that is the estate she inherited from her husband) she must give up to the heir the utensils which are fixed to the ground by nail or pegs. Also the main table with stools, the best wine measure and cask, kneading trough, basins and hatchet, the best cup, the coulter with share (cutting blade of a ploughshare) and the well bucket with the rope. All the rest she can dispose of by will or gift. She shall not be bound to answer for damage to buildings as long as she has not done it after the prohibition by the King.

This last rule does not really concern the market. We have included it to present the full set of these ancient rules. They show the concern of the Priory for the welfare of the inhabitants and probably stem from very real happenings.

The Annals of Dunstable are a precious source of information for many events of the Middle Ages. They relate events from all over the world and some local events which concerned the Priory and the Town in various ways. They are written in Medieval Latin and cover in detail the years 1201 to 1297(1). One third only has been translated and some sections are very difficult to understand.

There are many allusions to events concerning the Dunstable market. We will give here some of them, as they give insights to the life of the time.

In 1253, the wheat was sold, before the autumn, at 5 shillings a quarter — that is 60d or 25p for 512 pints. In 1258 the wheat is very scarce and the price rises, in Dunstable, to one mark per quarter - that is nearly three times more, and in Northampton to 20 shillings, that is four times more. The chronicler mentions that this year the Priory spent more than £80 for bread, drink and provisions.

The King's marshal, from whom the Prior was supposed to take standards for weights and measures, frequently visited the market to check the weights and measures used. On July 20 1274 every one of the bushel measures (8 gallons) in the town was found defective and the Town was fined four marks (£2. 66p)(3). They were given a new standard but at the end of the year they were again inspected and fined because there were still some short measures in the town.

In 1275 the brewers had broken the law either by short measure, low quality or excessive price, and the town was fined 40 shillings (£2). The author of the Annals of Dunstable Priory — the source of all this information — is pleased to mention “nothing wrong with the bushels this time”.

On 21th December 1278, the town was fined again by the King's marshal for false measures, probably used in the Christmas market.

In June 1279 the Bedford justices enquire about the clipping of coins. In the same year the butchers erected wooden sheds over the benches where they were selling meat, but as these were fixed to the ground, the prior and the town removed them. Later the sheds were allowed to be covered with foliage not set in the ground.

In 1286, the Prior — William de Wederhore — was summoned by the King's justice in Bedford to show by what warrant he claimed to have his privileges in Dunstable and elsewhere. The Prior answered that the town of Dunstable was his fief which he obtained by a charter of Edward I, the present king, this being the continuation of charters by Henry I, his ancestor, confined by Henry Ill, his son, in the first year of his reign, in 1227.

Amongst other things the rights of markets and fairs were questioned. The Prior gave the following rulings: a market is held every Wednesday and Saturday each week, and a fair held on First of August. He also mentioned that, in 1203, a fair of three days had been authorised by King John, grandfather of the present King, to be held on May 10 (St. Fremund's day) and the following two days. The Prior was completely exonerated and the court was fined 40 marks (£13.66) for false judgement. The expenses of the Prior for the trip to Bedford were £18 and 1 mark (£18.66) and in Dunstable £14.7s.3d. (£l4.36).

In 1290, the year the funeral cortege of Queen Eleanor passed through Dunstable, the bakers and brewers were fined 5 marks (£3. 33p) for using false weights and measures.

On April 13 1292, the King's marshal did his inspection in Dunstable. The town was fined for having too small measures and because the butchers had sold rotten meat,

The chronicler of the Dunstable Annals tells that, in 1294, the market of Dunstable and other markets in the area suffered very much from the stay of Prince Edward — son of the king — in St. Albans and Langley . Two hundred meals a day were not enough for his kitchen and he paid for nothing. His servants took all the provisions brought to market and even the cheese and eggs and any merchandise, even in the townsmen's houses. They left hardly anything. They took bread and beer from the bakers and brewers and forced those who did not have any to bake and brew. Later in the year the price of wheat in Dunstable increased to 16s.8d per quarter.

In 1295, after an exceptionally bad harvest and scarcity of corn, the bakers charged a very high price for bread. At the request of the people, the Prior, with the agreement of the community, had his bailiffs set the situation right and severely punished the bakers. Defects were also found in measures and fines paid.

In 1296, the Annals cease to be regularly kept, and so disappears this source of information.

After the dissolution of the Priory

Dunstable Priory was one of the last to be dissolved. The process of confiscation of the religious properties which started in 1536 allowed Henry VIII to refill the royal treasury. The properties were given to various favourites of the king. Gervase Markham, elected Prior of Dunstable Priory in 1525, was obliged to surrender his house in December 1540. In 1545 Richard Greenway was made keeper of the mansion, chief of the lands and gardens.

The dissolution of the priory implied the complete loss of privileges enjoyed by the townsmen under the prior's jurisdiction. The king who took his place as lord of the borough had nothing to gain by jealously guarding its administrative independence.

The burgesses might have forced the king to leave them some self-government at the beginning, but their hope of keeping some independence was frustrated when Dunstable was annexed, together with other Crown lands in Bedford , to the honour of Ampthill in 1542. Its status of “borough” was replaced by that of “manor”, attached to the royal manor of Ampthill to which the inhabitants owed service. The townspeople became tenants of the Crown. All the taxes and fines, tolls of markets and fairs, legislation on beer and bread, and other privileges exercised by the prior became the right of the bailiff. This was a man, appointed by the king, who acquired the lease of office for a variable number of years. We can get an idea of the profitability of the post when we know that it was leased in 1605 for 40 years at annual rent of £9.18s.8d., but in 1649 was said to be worth £24 a year, exclusive of various other privileges valued at more than £12 yearly.

The day-to-day management of a franchise market such as Dunstable naturally included the settlement of trading disputes, and these would have been dealt with by what came to be popularly known as Pie Powder Court . This was a temporary law court called in an emergency to sort out disputes which happened during the day. The name of that court comes from the French pieds poudreux (dusty feet) as it was a court for fairgoers and tradesmen who came in hot and dusty conditions sometimes from far away.

In general the problems encountered seem to have been the same as those of the Middle Ages: the use of wrong weights and measures, the disturbance caused by the market and the arrival of newcomers who had not paid for the right to be there. The regular stall holders had dug themselves in, with probably some customary rights to make use of a particular pitch. This is shown by a ruling from the middle of the 18th century which declares that “every person who shall set out a stall in the Market or Fair held in this town or a any other time or places within this Manor and have not been accustomed to do so for 40 years past shall therefore forfeit and pay to the Lord 10 shillings”.

The ownership of the manor passed to various families during the next two centuries. We can mention the Bruces, Earls of Aylesbury, in the 17th and 18th centuries. An agreement dated from December 1738 between Lord Bruce and John, Duke of Bedford, of his leasehold estate (99 years) refers to the site of the old market (in the middle of High Street North ) as being part of the waste of the Manor Royal. In January l771 the Duke of Bedford obtained a lease of the manor for three lives (99 years) which was renewed to Gertrude, Duchess of Bedford, in 1773.

In 1801 the Dunstable Road Act authorised the Turnpike Trustees to demolish the Old Market House – the area was called Market Place - and to remove the material on condition that they erected another Market House as near to the old site as possible. This Old Market House was situated in the middle of High Street North , near the crossroads. It was a part of Cooke's Row, which was erected in the middle of the 16th century as the equivalent of Middle Row in High Street South . The new Market House was erected in the emplacement of the present Abbey Bank, just next to the old Anchor Gateway.

This Old Market House is clearly seen on the so-called “Duke of Bedford 's Map” surveyed by T.Bateman in 1762 and now deposited in Bedford County Records Office. It is square and about 2m on each side. From top to bottom it covers Houghton Regis down to Dunstable centre. The scale is approximately 12,500 : 1). The section showing Dunstable centre is reproduced here.

Dunstable Borough

The ownership of the Manor of Dunstable returned to the Crown in 1839. A judgment of 1855 (AG v Barker) is worth mentioning. It held that the streets of the Manor of Dunstable, including the old market strip between West Street and Albion Street , were part of the Manor and the ground remained in the Crown as Lord of the Manor.

Eventually the Manor of Dunstable recovered its ancient status of Borough in 1864, with the charter of Queen Victoria . This charter of incorporation vested the government of the town in a mayor, four aldermen and twelve councillors, one-third of whom retire annually.

The first municipal elections for the Borough Council took place in 1865; in the same year the commission of the Peace was issued and the first JPs appointed. The following year the Borough Police was established.

One of the new Council's first actions was to buy the Market House from the Crown for Council Meetings and a Police Court (Magistrates' Court) in 1866.

Three years later a clock tower was erected on the building and in 1872, a corn exchange and a plait hall were established in the Town Hall in the Anchor Yard. Most of this Town Hall was burned down in 1879, and a second one was built on the same site, using the original facade. It was opened in 1880 and was pulled down in 1966.

In 1867 an agreement (indenture) is passed “between the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty (Victoria) of the first part, the Honourable Charles Alexander Gore a commissioner of Her Majesty's Woods Forests and Land Revenues in charge of the Land Revenues of the Crown in the County of Bedford of the second part, and David Scott of Dunstable, butcher of the third part, witness that, in consideration of the yearly rent hereafter reserved...” This very long text simply means that, from this date, David Scott can collect the tolls of fairs and markets held within the Manor Royal of Dunstable for a term of 10 years and, for this privilege, he will have to pay a yearly sum of £70 in four instalments.

In 1870, the Corporation purchased the Manor and Market subject to the lease dated 1867 with David Scott, for the sum of £150. The same year the Crown transferred the land of the Manor Royal to the Mayor and the document of transfer gives an interesting list of exceptions of privately owned properties through the town.

In 1871 Charles Benning, solicitor acting as agent to the Mayor, purchased from David Scott the stalls, hurdles and other articles he had been using in connection with the market since 1867.

An important document is published in 1871 by the Dunstable Local Government Board. Here follow some of the 15 rules given in the document.

1. A Market shall be held on Wednesday and Saturday in each week for the sale of Straw-plait, Straw-plait Goods, Corn, Wool, Hay, Straw, Cattle, Sheep, Goats, Swine, Horses, Mules, Asses, Fish, Poultry, Meat, Fruit, Vegetables, Provisions, Goods, Agricultural Produces, Implements, and Merchandise.

2. A Statute Market shall be held once a year for ever, on the fourth Monday in September, for the hiring of Servants and labourers in Husbandry, and for the general purpose of a yearly Market, for the sale of Goods, Meat, Fruits, etc.

3. Four yearly Markets shall be held in each year for ever, on Ash Wednesday, the twenty-second day of May, the twelfth day of August, and the twelfth day of November, for the sale of Cattle, Sheep and all other Goods and Merchandize..,

4. The Markets shall be held in High Street North , High Street South , West Street , and Church Street , and in such other Public Streets and Highways and in such parts and spaces as the said Local Board may from time to time direct. The Auction Sales shall take place in such places, spaces, and localities, as the local Board shall from time to time direct.

5. The Markets shall on Wednesday begin at Nine o'clock in the Morning, and shall be closed at Six o'clock in the Evening, and on Saturdays shall be closed at Twelve o'clock in the Evening in each week. . . booths, caravans, stallage, and other erections, shall be cleared off and removed by Twelve o'clock at midnight. The time of opening and closing of the Market on Wednesday, shall be announced the ringing of the Market Bell ...

6. Stalls, Stallages, Trestles, Standings, and Hurdles will be provided in the markets by the Local Board.

9. No person occupying any Stall, . . . shall suffer any dirt, rubbish, litter, garbage, oyster shells, or refuse, to remain under or about the same respectively… and all dirt, rubbish, . .. arising from the sale or cleansing of animals, game, fish, vegetable shall be immediately put into a proper tub or basket, which shall be provided...

13. No wagon, cart, truck, trolley, or barrow shall stand in any of the streets near, adjoining to or in the market for a longer period than is necessary for loading or unloading, and must thereafter be at once removed.

15. Every person offending against any of the above Bye Laws shall forfeit and pay for every such offence a penalty not exceeding Five Pounds.

Changes of venue

In 1964 the council removed the rights to hold a market on “a strip of land between the pavement on the South West side of High Street South and the trunk itself”. The cattle market, which had been held there traditionally for many years, had ceased to function in 1955. The market could not continue, reduced as it was, on the pavement on the west side of High Street North . So at the same date of 1st April 1964, the new market opened in front of the new Civic Centre which had recently been opened.

Some people did not appreciate the change and for some months Mr. F.C. and Mrs. J.E. Cuss had to be given notices that they were 2infringing market rights of the corporation and trespassing on the site of the former market property of the Corporation by trading from a van equipped as a mobile shop on the site of the former market at High Street North, on both market and non-market days.”

In 1987 the market moved to the north side of the Queensway Hall, where fixed stalls were installed.

In 1996 a Friday market started with much success in the small area of Ashton Square between the Methodist Church and Wilkinson's. In July 1997 the Town Council backed the plan to extend this area into the adjacent car park and into The Square after the taxi rank and the bus station were relocated.

“Stallholders say the benefits of moving the market are considerable,” reported the Dunstable Gazette of July 2 1997. Shoppers would be more likely to visit it as it would be on a through route to the town centre, it would add interest to the area and be close to public transport. Chairwoman of the market, Diane Naylor, added: “The market needs a certain volume of pedestrian traffic to remain viable to traders. Because it is a long way from the banks, building societies and shops, we lose a large part of the floating shoppers and the impulse buyers and if the weather is bad we are particularly hard hit.”

In 1999 the market was removed from the Square, in front of the Methodist Church , and expanded into the car park up to the Methodist bookshop. The Millennium clock tower was built on the space along High Street South .

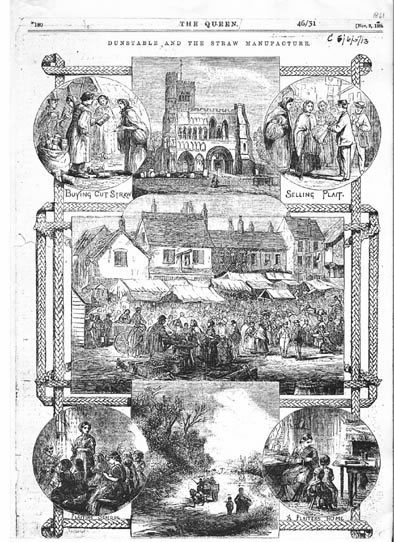

Dunstable Straw Plait Market in 1861. The engraving above

was published in the magazine “The Queen”. The left and centre buildings are the pub ‘The Nag's Head', at the corner of

West Street and High Street North. On the extreme right hand

side of the drawing one can see the front columns of the Town Hall.

The cross roads was completely blocked to traffic.

FOOTNOTES

1. The first part of the Annals starts in AD. 1 and gives a brief survey of the Church history up to 1201. In 1202, the text becomes original and was written by Richard de Morins, the 4th Prior, until his death in 1242. The following chroniclers are not known. The detailed chronicle stops in 1297 but there are some odd reports of events until 1459 on the blank leaves at the end of the document. The last entry is a declaration made in Dunstable by Henry VI.

2. A quarter equals 8 bushels, each bushel being 8 gallons. A quarter is thus 64 gallons or 512 pints or about 291 litres. The quarter was mainly a unit of volume for dry substances like wheat In weight a quarter of wheat was approximately equivalent to 510 lb or 230 kg. This would put the price at 0.lp per kg if we use present-day units.

3. The pound sterling was the value of one pound weight of silver. It was divided into 240 small pieces of one penny each. Three marks were £2. So one mark was 2/3 of a pound sterling or 13 shillings and 4 pence, or in the present money between 66 and 67p.

It is difficult to make a valid comparison with the present day because the social and economic structure of the Middle Ages was so different. In the 13th century an untilled labourer was earning 1/2p a day, a skilled carpenter made l½p, a prosperous freeman could live on £4 a year.. So to have as idea of the real value of the money we have to multiply the figures quoted by a factor of 500 with the possibility of making mistakes from half to twice the value!

A computer-enhanced view of Dunstable town hall as it would have looked not long after it was built in

1864, before a tower was added in 1869.